It takes a village?

We talk about community, but 21st century parents put more pressure than ever on ourselves.

Good morning and welcome back to Creative Parenting Club. Thanks for being here. Today, we’re back with another essay, inspired by a famous book that became an unexpected source of parenting insight.

Enjoy and be sure to let us know what you think! We’ll be back with our latest interview next week.

In case you missed last week’s post about Berlin-based parents and co-founders Lisa Hubner and Jeffrey Moreno, you can check it out here.

Have a great weekend everyone!

100 years later

By

—

Want to feel some creative parenting envy? Let’s take a trip into the past.

Fans of Ernest Hemingway — or of Paris in its heyday — might be familiar with A Moveable Feast, the pocket-size memoir of Hemingway’s life in Paris with his (first) wife and young son from 1921-1926, during one of the most famous cultural periods in the history of one of the world’s most famous cities of culture.

The book, written years later and published in 1964 after Hemingway’s death, is known for its portrayal of the many famous creators with whom the author crossed paths: luminaries like Gertrude Stein, Ezra Pound and F. Scott Fitzgerald. But it also chronicles a particularly formative time in Ernest Hemingway’s own life. Aged 22 to 27 during the years covered by the memoir, at the time Hemingway was still an aspiring writer making most of his money from freelance journalism. He had not yet published any books.

I started A Moveable Feast late in 2023, during a phase of peak parenting intensity around the time my son turned 1 and his older sister was approaching 3 1/2. I’d always wanted to read it, and when I saw that it was only 130 pages, it seemed like the kind of book I could handle at the time.

What I wasn’t expecting was the unforeseen lessons it would hold about creative parenting.

Over the course of A Moveable Feast, we get an intimate glimpse into Hemingway and his wife Hadley Richardson’s life together as a young artist couple getting by. There are passages about the cold, hard winters and the luxuries of securing enough firewood to heat their small apartment. There is a chapter where Hemingway, a famous fan of horse-racing (and really any sport involving large animals), talks of going to the race track and wagering his latest journalistic earnings, the winnings turning themselves into enough money to pay for the next few months of adventures.

What we don’t learn until later in the story: for much of this time in Paris, Hemingway and Richardson were also taking care of a young child.

Though born in Canada, Ernest and Hadley’s son Jack (nicknamed Bumby) came back to Paris on a 12-day voyage across the Atlantic Ocean with them when he was just a few months old.

The parenting norms back then were a little different.

In the last chapter, we learn about what the young Hemingway parents would do during Bumby’s first Parisian winter when they couldn’t find a babysitter:

I could always go to a café to write and could work all morning over a café crème while the waiters cleaned and swept out the café and it gradually grew warmer. My wife could go to work at the piano in a cold place and with enough sweaters keep warm playing and come home to nurse Bumby. It was wrong to take a baby to a café in the winter though; even a baby that never cried and watched everything and was never bored. There were no baby-sitters then and Bumby would stay happy in his tall cage bed with his big, loving cat named F. Puss . . . F. Puss lay beside Bumby in the tall cage bed and watched the door with his big yellow eyes, and would let no one come near him when we were out and Marie, the femme de ménage, had to be away. There was no need for baby-sitters. F. Puss was the baby-sitter.

The book meanwhile ends with an idyllic description about the family traveling to the Austrian Alps for Christmas. The Hemingway parents didn’t seem to have any issue taking time for themselves while traveling with their child:

Schruns was a healthy place for Bumby who had a dark-haired beautiful girl to take him out in the sun in his sleigh and look after him, and Hadley and I had all the new country to learn and the new villages, and the people of the town were very friendly.

The whole book is about how poor Ernest Hemingway and his young wife were at the time. But in 1920s Europe, even a starving artist couple could afford a traveling nanny.

And when there was no nanny to be found, apparently it was acceptable to leave your baby home alone with his cat.

Today’s parents have it different

Around the same time as I was reading A Moveable Feast, I came across another interesting piece of writing.

You read that right. In the author’s words:

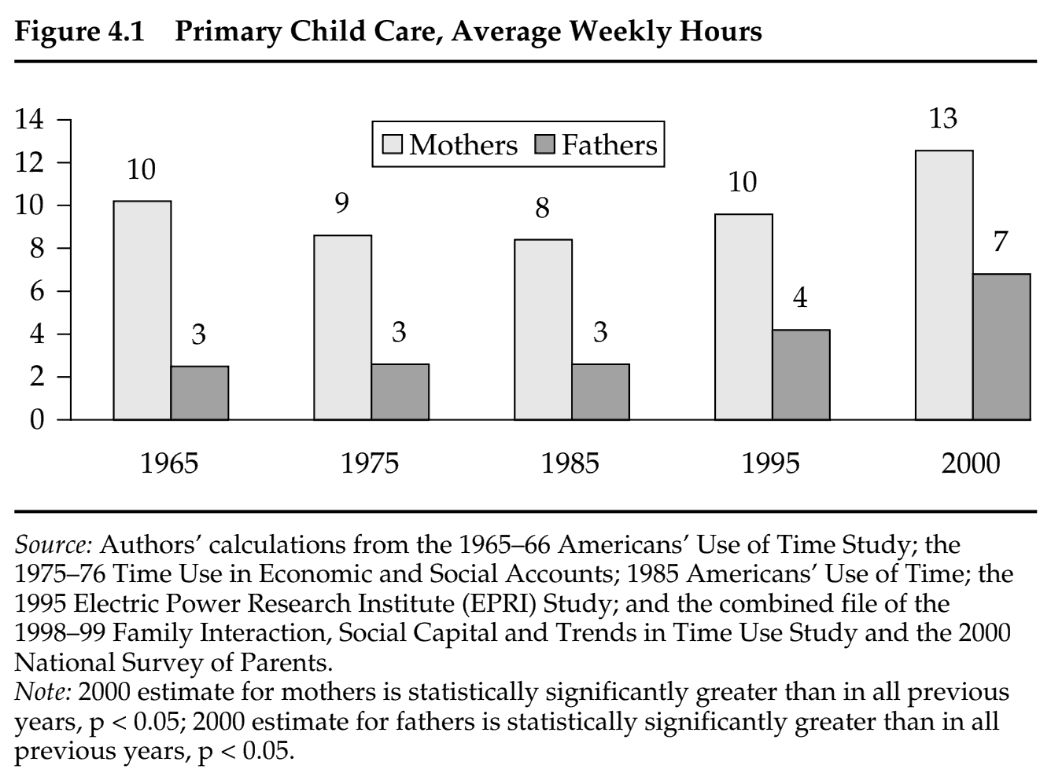

Working moms spent as much time on focused childcare (10.6 hours per week) in 2000 as stay at home moms did in 1975 (10.7 hours per week). This only counts time when childcare is the primary activity. That is, if you are cooking while keeping an eye on the kids, it doesn’t count as focused childcare.

Dads today spend more time on focused childcare, too — though, mercifully, that’s less surprising. One would hope today’s dads are more involved than the 1950s version.

But even allowing for gender role imbalances, the part about moms seemingly makes no sense. More moms work outside the home than ever before — so how is it possible that working moms also spend more time with their kids?

The cost of domestic childcare is one explanation.

But social pressure explains a lot too.

Somewhere along the way, “being a good parent” turned into an expectation that we’re always on when our kids are present. Whether it’s following our kids around at the playground or parents stepping over themselves to solve every minor playdate disagreement, it feels like there’s this constant urge to curate our children’s childhood, making sure that every experience has some kind of future value.

As Ruth Grace Wong, the author of the article above, writes: “parenting is much more intense now that it has been in the past.”

Despite the fact that kids today, empirically, get more attention than ever from their parents, parents today — moms as well as dads — are socialized to feel guiltier than ever when we feel like we’re not giving them enough attention.

Many parents are lonelier than ever, but we sacrifice other important social relationships because we’re locked into thinking that we need to be spending even more time with our kids.

And when we do feel like we’re doing enough, we often feel inadequate for letting our own hopes and dreams slip.

What can we learn from all this?

It isn’t about Hemingway

I’m not here to glorify the parenting norms of 100 years ago (though leaving your baby at home with the cat is still kind of a flex).

Ernest Hemingway may have been a good father for his time, or maybe not. He didn’t turn out to be the best husband: in 1927, after one of those trips to Austria, he ran off with a friend of the family, leaving Hadley with their three year-old and half the royalties of his first novel.

But this isn’t actually about Hemingway, or any parent from previous generations.

It’s about the way we expect ourselves to parent today.

It’s about the creeping sense that we’re supposed to be everything to our kids and still somehow fulfill our personal dreams while making it look easy.

It’s about the way that parents give up on the things in life that we enjoy, telling ourselves we are sacrificing for our children when this isn’t what we actually want.

It’s nice that today’s parents spend more time with our kids. It’s cool that we’re more engaged. It’s good that we prioritize our kids’ emotional well-being, try to break generational cycles, that we’re committed to raising them with thoughtfulness and care.

But many of us also live farther away from extended family than past generations. The average kid has fewer siblings and cousins to run around with than they once did.

As parents we have less support, less professional and financial security, more job pressure and more social pressure to be constantly available.

Meanwhile, in the summer of 1924, Ernest Hemingway and Hadley Richardson left their six-month-old with a nanny while they traveled to Spain for the Running of the Bulls (the cat was busy).

Maybe we can all chill out a little bit about how early or late we pick our kids up from daycare.

About that village…

If you’re like me and you also struggle daily to juggle your creative aspirations with the daily demands of work, family and everything else in your life… please join me in taking a deep breath.

Parenting in the 21st century is hard. We’re all doing our best. And none of us should feel bad for feeling like we can’t always do it all.

Very few parents have a literal village anymore, but we do have more support than we often give ourselves permission to lean on.

Maybe the village is one more hour every day at daycare. Maybe it’s a playdate exchange with another family in the neighborhood. Maybe it’s a little bit of extra screen time so that we can have a few more minutes of focus time. Maybe it’s learning to get better at ignoring our kids.

Modern parenting is full of high-stakes anxieties about whether all the little decisions we’re making today will have a positive or negative impact on our children’s future.

The truth? Most of it probably won’t matter at all. The big stuff is far more important.

So whether it’s about setting more realistic expectations or accepting that no one does this perfectly, let’s remind ourselves that yes, the world does seem to expect more of us parents than ever before. But too often, we also expect way too much of ourselves.

And while we can’t do much about the former, we can push back against the latter and reclaim the permission to pursue our own needs.

Somehow, the right balance between creative goals and family will find a way of materializing.

And our kids will be just fine.

****

Cover photo credit: Anduze traveller (Flickr)

At Creative Parenting Club, we're all about helping parents find the middle ground between high stress parenting and leaving your baby with the cat.

Thanks, Matthew. We do put a lot of pressure on ourselves as parents these days, and while this allows us to protect our children from many harms, at some point it can stifle their growth and our overall joy as a family. Good to remember that the human race has survived through many times and cultures and that the "big stuff," as you mentioned, is the most important.

I've been thinking lately about how when we parent our children, it's not just about parenting; it's also about modeling adulthood to them. It's possible to sacrifice so much for our children that they will succeed, sure, but they will also never want to have children of their own. My daughter needs to see that I can be a good dad while also taking some time to write, so that if she wants to write someday she will not see that as incompatible with being a mom.

I'll also mention that there are many individuals today who are struggling to even get started in parenting. Here in the US, nearly 1 in 4 children live in father-absent homes, which leads to a host of big problems. With this in mind, it really matters how we model the basics - encouraging a more approachable precedent for involvement.